Published on | General

As 2025 marks 30 years since the introduction of the National DNA Database (NDNAD), we thought we’d take a look back and share some information on how this vital crime fighting tool has developed both locally and across the UK.

Many people will be aware of Dr Alec Jeffreys’ discovery in 1984 that enabled him to develop DNA fingerprinting, which allowed suspect DNA to be matched to samples left at crime scenes. This was first used in a criminal case in the UK in 1986, when Leicestershire Police asked Dr Jeffreys’ to verify the prime suspect’s confession. The DNA test exonerated the suspect, and through mass genetic testing of men in the local area, Colin Pitchfork was eventually arrested after persuading a friend to take the test for him. The man was overheard talking about it in the pub and the police were informed.

Pitchfork wasn’t convicted until January 1988 however, and in the meantime in 1987, an individual named Robert Melias was convicted of rape in November 1987 at Bristol Crown Court after his DNA matched evidence found on the victim’s clothing. Faced with the forensic evidence, he admitted the rape and five burglaries. So, whilst Pitchfork is the first individual convicted of murder using DNA, Melias actually holds the Guinness World Record for being the first person convicted on the basis of DNA evidence.

But what about the West Midlands? Well we were very close behind – in April 1988 Angus Needham was convicted of two rapes and eight sexual assaults, following a 22-month reign of terror across several tower blocks in the Birmingham area. He would lie in wait for his victims, near the lifts in the tower blocks and target women returning home alone. DS Denise Dugmore who ran the incident room out of Steelhouse Lane Police Station, took victims out regularly in a patrol car, to see if they could spot him, and eventually their efforts paid off when he was spotted in Newtown. He was convicted and sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment.

It would be another seven years before the NDNAD was established, right here in Birmingham laboratories. The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 re-classified saliva as a non-intimate sample, paving the way for the national database. The multi-million pound project was initially overloaded with samples sent from police forces after it commenced its work, and there were reports of a huge delay building after the initial estimates proved wildly inaccurate. Additional staff and a shift system were introduced in order to try and deal with the backlog.

Initially, only samples taken from people charged with a recordable offence could be taken, and they had to be deleted if the individual was acquitted. Wider use of DNA as evidence and speculative searching, including thousands of samples improperly retained on the database, led to increased police powers to retain such samples. This was not without controversy though, and continued debate on the retention of DNA samples and wider debate about retention of criminal records (despite these being significant in the identification of many serious sexual and violent offenders), continued throughout the 2000s.

By 1997, West Midlands Police was being heralded as a national leader in its scientific expertise, with one of the best DNA success rates. Around 650 samples taken from suspects between 1995 and 1997 had been matched to crimes in the region, 170 to outside forces and 342 ‘scene to scene’ matches. The force was stated at having submitted 16,000 samples to the database and had achieved 1,000 hits since 1995.

In 2005 it had 3.1 million profiles and in 2020 it had 6.6 million profiles (5.6 million individuals excluding duplicates). There were 731,000 matches of unsolved crimes between 2001 and 2020.

The ongoing debate between police powers and public scrutiny over privacy concerns eventually culminated in the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, which significantly curbed the indefinite retention of records, genetic and biometric information. 270,000 samples were added to the database in 2019–20, populated by samples recovered from crime scenes and taken from police suspects. 124,000 were deleted for those not charged or not found guilty.

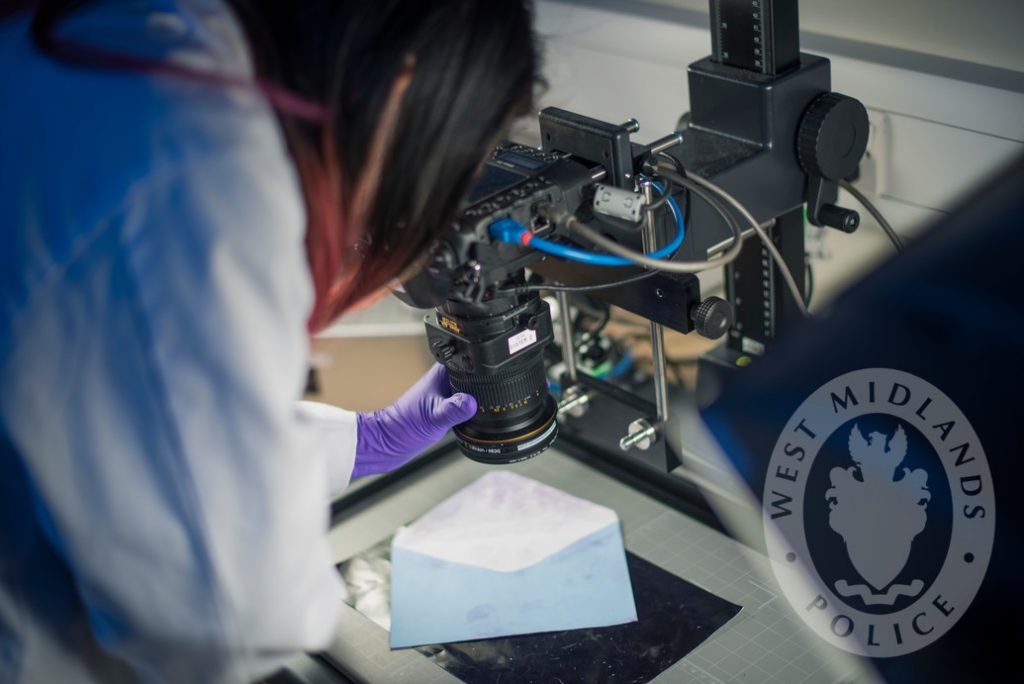

Techniques to extract DNA have significantly improved since 1995 – back then a blood stain the size of 2p coin was needed to extract sufficient information. Nowadays a pinprick of blood is all it takes.

The extent to which DNA is analysed has also increased considerably: back in 1995 SGM profiles were used, which exampled six areas of DNA and a sex-typing marker. SGM Plus improved this significantly to 10 regions (loci) and a gender marker. Nowadays DNA-17 is used: a forensic DNA profiling technique that analyses 16 specific areas of DNA, plus a gender marker, to create a unique profile. It’s superior to older methods like SGM Plus because it provides greater sensitivity and can analyse degraded or low-quality DNA samples. This allows for more accurate and complete DNA profiles from crime scenes and can help link offenders to multiple crime scenes.

West Midlands Police has continued to use advances in forensic techniques in cold case reviews, as well as current investigations. The recent conviction of Michael O’Meara in Coventry in December 2024, for a rape 35 years earlier, shows how DNA can be pivotal in securing convictions even long after offenders think they have gotten away with it.

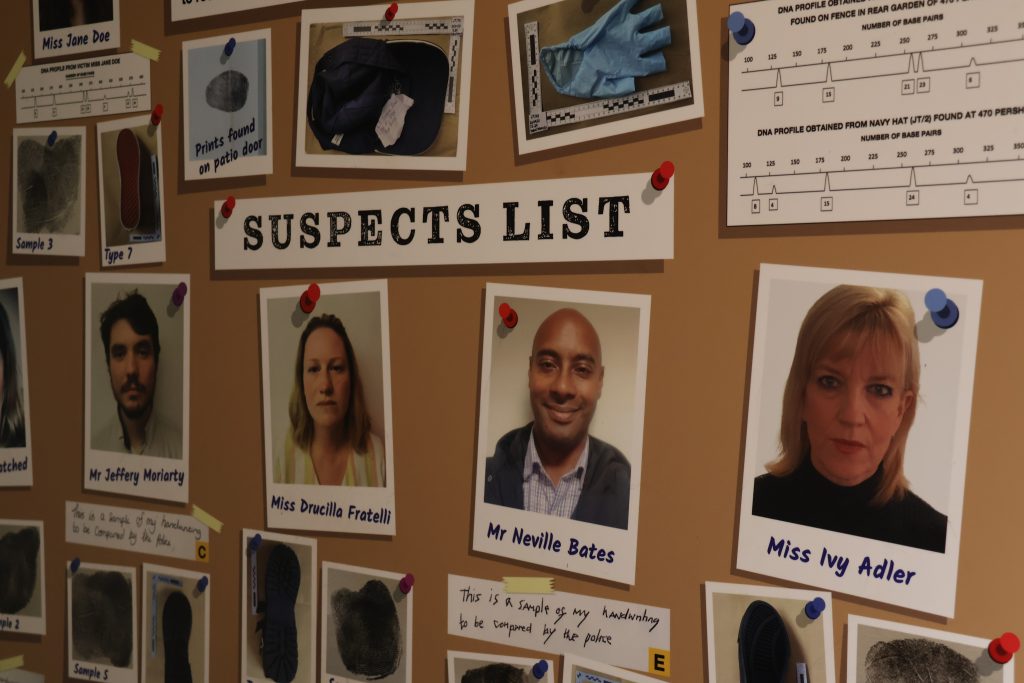

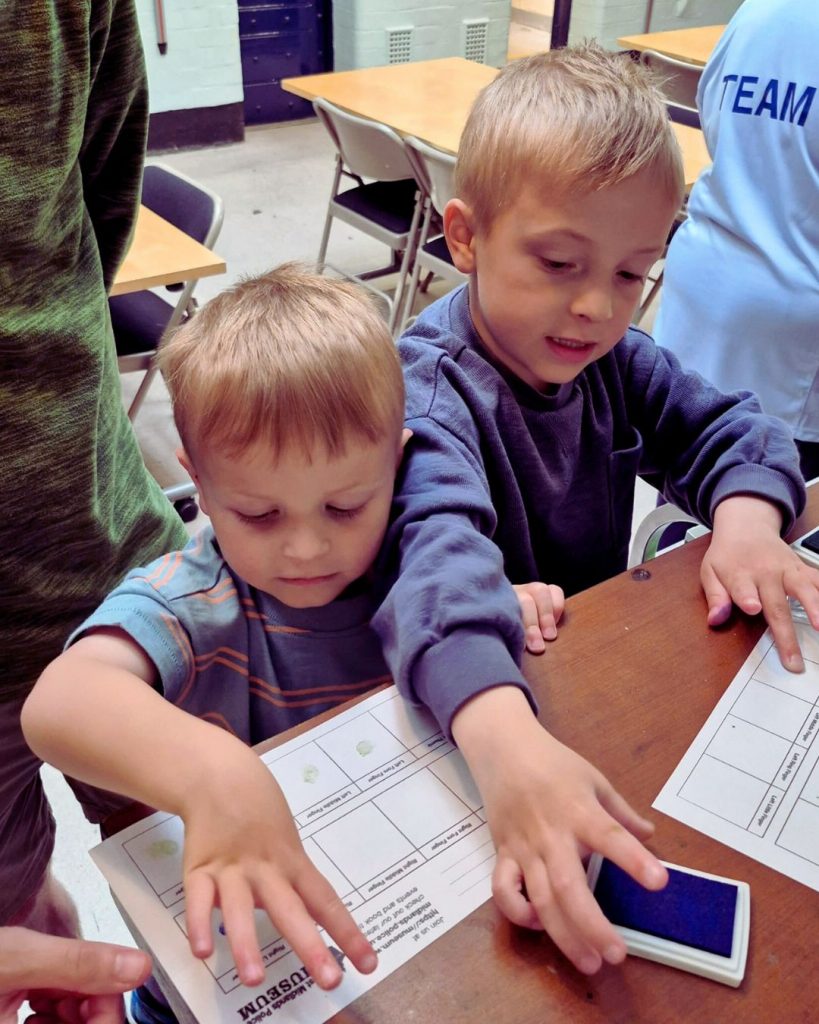

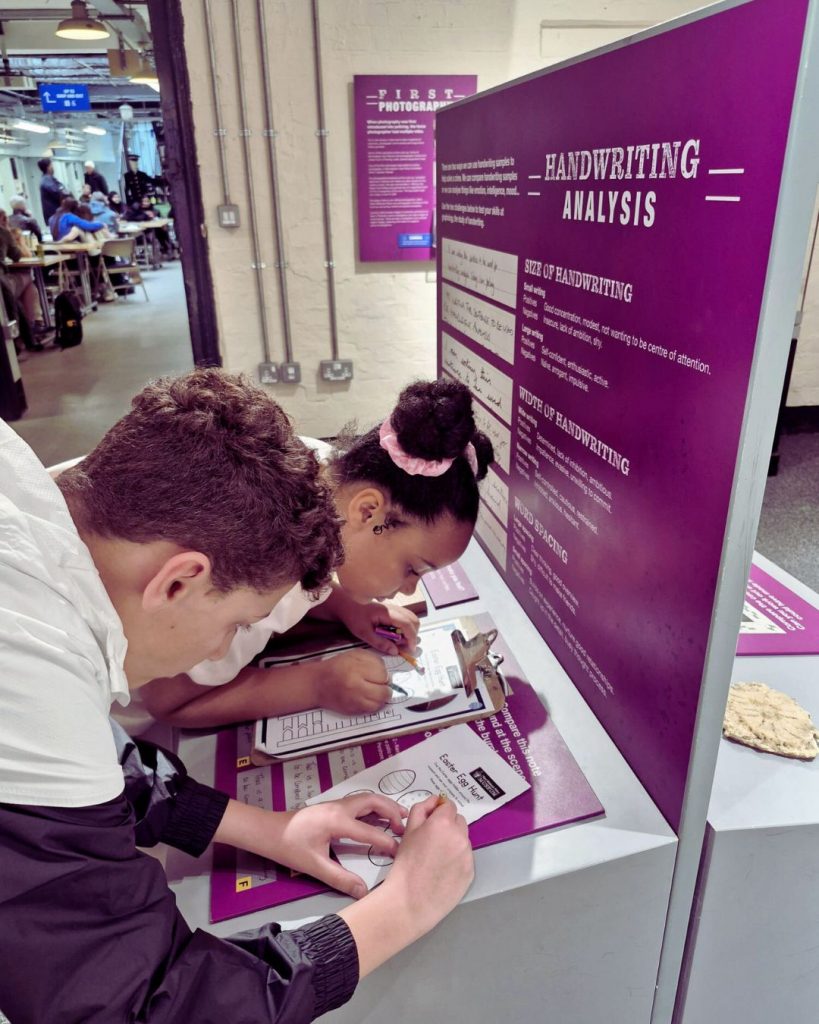

Here at West Midlands Police Museum we explore the history and usage of DNA evidence through interactive trails and family activities.